What exactly does it take to create an artwork? What conditions need to be met for an artist to take ownership of an object? The precedent set by Duchamp seems to suggest that all an artist needs to do is to stake a claim to a thing, that the relevant part of artmaking is not the act of constructing an object, but creating an idea. Art history seems to confirm this claim, but is this valid? What and where exactly are the limits?

I've been thinking a lot about the recent Tino Segal show at the Guggenheim, and what exactly it means for him to claim artistic ownership of a couple embracing, as he does in his piece Kiss. Here Segal takes a ubiquitous human activity and stamps it as his own. Does he get away with it? And is it really art? Or, perhaps more importantly, is the 'artness' of it really a meaningful question? Perhaps what is relevant now is not the question 'is it art,' but rather 'should we care.'

Fortunately there's an iphone app that can help with these questionable cases of artistic identity. The pocket-sized program analyzes your photos and calculates if whatever you're looking at is, in fact, art. (Unfortunately this will be little help in with Segal case, who has prohibited photography of his pieces.) While this app might be the latest gag put out by the Pittsburgh based Mattress Factory, the tongue-in-cheek tech piece asks a larger and more serious question: to what extent is the label 'art' an interesting and relevant distinction? If the Duchampian vision of obliterating the line between life and art has indeed been successful - and we can argue with some conviction that it has been given a few colorful examples like living sculptures Gilbert and George - is there any sense in labeling something art at all?

Untitled (AfterSherrieLevine.com/2.jpg)

Michael Mandiberg, 3250px x 4250px (at 850dpi), 2001

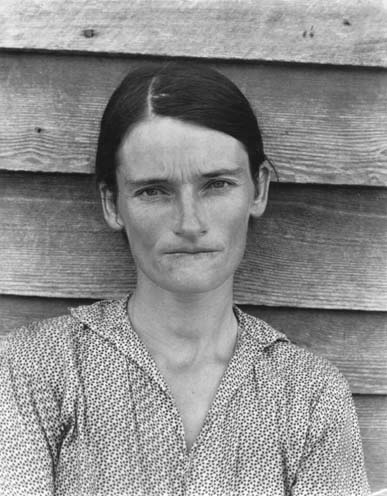

What, if any, are the limits of this? How about claiming someone else's art as your own? Sherrie Levine has made a career out of this, rephotographing Walker Evans depression era photos in the late 70's, and later reproducing Duchamp's Fountain in gold. Her move was repeated in the early 2000's by Micheal Mandiberg, who scanned both the Evans and Levine photographs and uploaded them to his website where they can be printed with a certificate of authenticity as original Maniberg's.

What about having someone make every part of your work for you? Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons have been doing this for years, and while it may upset the likes of Dennis Dutton and Stuckism International, the art world at large seems to ask few questions about these objects.

Call me young and naïve, but intuitively I'm still somewhat uncomfortable with an artist who claims ownership of other people's work. I certainly don't want to advocate throwing them out of the pantheon of art, but I think it's very important that we consider who actually made the artwork as part of the piece's conceptual core. Part of the value of Warhol's commentary was that he wasn't making his objects, and that they would have meant something different if he was. The question going forward is whether or not this same applies to artists like Jeff Koons, Gerhard Richter, Kehinde Wiley, or Tino Segal. Whether their participation, or lack of participation, in the creation of their artwork helps or harms the piece itself.