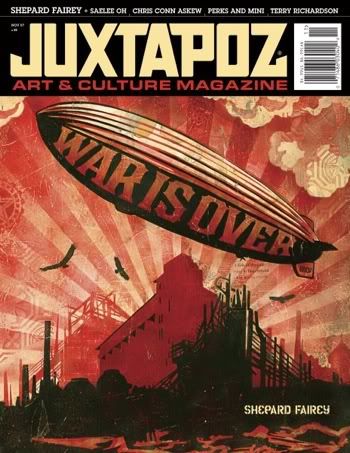

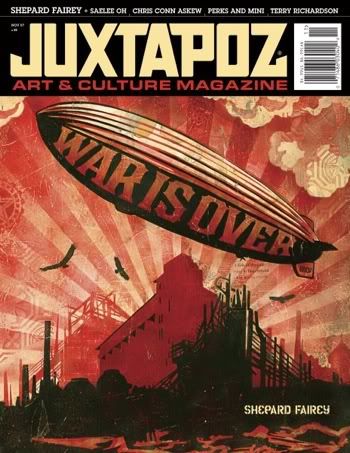

Issue of Juxtapoz Magazine

Cover art by Shepard Fairy"A frog is either lowbrow or highbrow.

If you catch it, it's low. If you order it in a French restaurant, it's high."

-Unidentified chef, from Burkhard Bilger's Noodling for Flatheads

In 2007, commenting on the blog

PaintersNYC, artist

Kelli Williams observed that it's hard to be a

Juxtapoz artist "in an

ArtForum world."

Juxtapoz is a popular magazine dedicated to showcasing contemporary "

lowbrow art." It was founded by the artist

Robert Williams in 1994. The "

ArtForum world" of Kelli William's statement references the magazine of that name, but also the "high art" scene it covers, of which

New York City, for the time being, remains an - if not

the - epicenter. Until recently, the artwork featured in

ArtForum was very different from that seen in the pages of

Juxtapoz.

Juxtapoz is representative of the

Los Angeles art scene, and the U.S. west coast scene more generally, where the aesthetics of

pop surrealism,

folk art,

post-graffiti, or

street art are wholly embraced.

But artwork infused by

Juxtapoz's colorful spirit is no longer uncommon in New York galleries.

Andrew Schoultz,

Tim Biskup, and

Jeff Soto, talented west coast artists regularly lauded in the pages of

Juxtapoz, today exhibit with the

Morgan Lehman and

Jonathan Levine galleries, and influential post-graffiti artist

Barry "Twist" McGee is represented by the renowned

Deitch Projects. Jonathan Levine makes plain his dedication to the post-graffiti aesthetic; his gallery's website states that its mission is to exhibit "work influenced by illustration, comic books,

graffiti art and pop imagery." Perhaps it's no longer so hard, then, to be a

Juxtapoz artist "in an

ArtForum world"?

But, more importantly, does lowbrow art require the affirmation of the "high art" world - for easy contrast, let's call it highbrow art - in order to be considered mainstream or legitimate? If so, what exactly is the cultural significance of highbrow art to the world at large?

Jeff Soto

Jeff Soto

"Purple Heart"

2007

Acrylic on wood

12 x 12 inchesThe commercial success of books like

Beautiful Losers: Contemporary Art and Street Culture and

Wall and Piece, the latest offering from the infamous

British artist,

Banksy, suggest that pop surrealism, post-graffiti, and street art succeed in connecting with the multitudes. On the other hand, it's an uncontroversial fact that highbrow art generally

doesn't move the masses (with the exception of its remarkable ability to offend the religious sensibilities of

the Christian Right and

certain mayors). But highbrow art doesn't simply fail to connect with the general population; the fact is, most folks sneer at, mistrust, or resent

ArtForum's world.

Perhaps because they feel beleaguered by popular tastes, many players in the world of highbrow art - artists, gallerists, critics, and curators alike - reject the influx of pop surrealism and post-graffiti flavor. But their objections will inevitably prove inconsequential; as

the Borg of "

Star Trek" put it, "resistance is futile." Even if some of the more esoteric subcultures of the

Juxtapoz arena -

Tiki culture, for example - are unlikely to find a toehold in the world of "high art," the graphic influences common to post-graffiti work already inform the paintings of contemporary art world darlings like

Dana Schutz,

Marcel Dzama,

Trenton Doyle Hancock,

Ryan McGuinness,

Lisa Yuskavage,

Yoshitomo Nara, and

Jules de Balincourt. (In fact, Dzama and McGuinness have been featured in

Juxtapoz; it won't be long before other celebrated highbrow artists are, too. One wonders if the lowbrow label will be applicable for much longer.) And then there are artists like

Judith Schaechter, whose

stained glass works were lauded in the pages of

Juxtapoz years before her work hung in

the Whitney Museum or before she received

Guggenheim and

National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships.

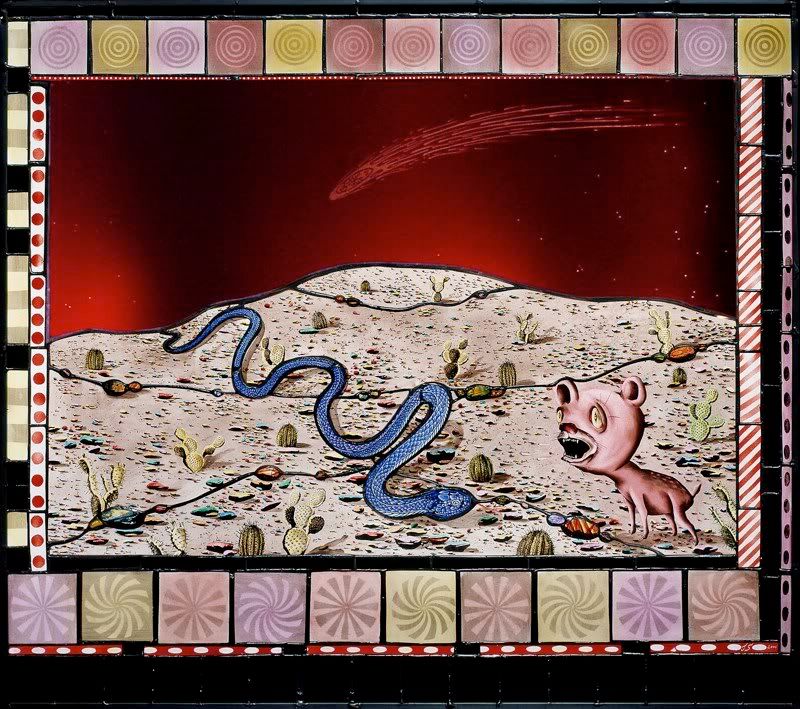

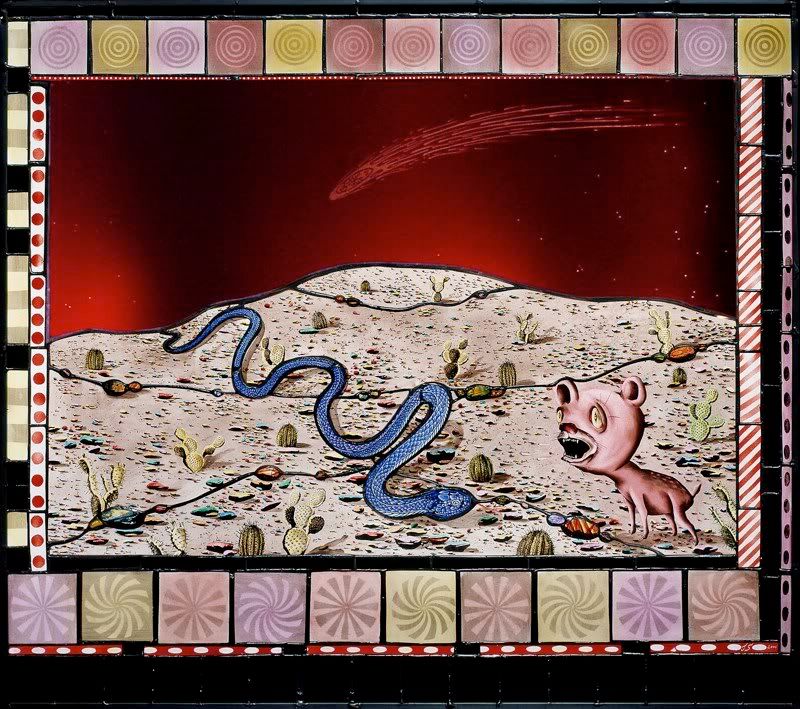

Judith Schaechter

Judith Schaechter

"Hyena Snake Comet"

2004-2008

Stained glass

30 x 33 inchesMuch of the highbrow resistance to pop surrealism and post-graffiti is rooted in the self-identified elites' distrust of populism. Comic books and strips are intended for mass consumption, but graffiti is unquestionably the most populist of the lowbrow tributaries. No art form has fewer barriers to entry; all you need is a can of spray paint and a little

chutzpah. Ask someone knowledgeable about the subject to relate the history of modern graffiti, and you'll likely hear an abridged version, one that begins in the 1970s, in and around New York City's

Bronx River Houses, and runs parallel to the development of

hip hop. City funding for arts and culture programs was pitifully low at the time, and enterprising teens looked for new ways to entertain and express themselves. As

Lady Pink, an influential graffiti artist of the late 1970s and 1980s, explains, graffiti was the most available "forum for free speech."

Of course, the human urge to make marks predates the Bronx River Houses by millennia. Our ancestors

depicted their quarry on cave walls and, more recently,

citizens of ancient Rome scribbled their political opinions on market stalls (hence the word's etymology, from the Italian

graffiare, meaning "to scratch or scribble.") But during the early days of modern graffiti's ascendancy, practitioners prioritized ego over observation or socio-political commentary. The pioneers of the 1970s and 1980s graffiti scenes in New York City and

Philadelphia -

Taki 183,

StayHigh 149, Cat 161, and

Cornbread, among others - were primarily known for their "tags," stylized monikers spray painted on walls and subway cars. They vied for renown by tagging as many surfaces as they could, and walls that were difficult to access had a special cache. The competitive behavior of these early graffiti "artists" might be best described as

base scent marking, activity essentially indistinguishable from the industry of the bored high school student who scratches "(x) was here" on the wall of the bathroom stall. Fortunately, as more artists entered the nascent graffiti scene, such adolescent "battling" became insufficient impetus; soon, the egotistical tag evolved into something more colorful and complex. Artists added characters, often comic in nature, a result of their limited palettes and time frame, and, before long, these characters evolved into "pieces" (short for masterpieces). The best graffiti artists came to value style and artistry as much as placement.

The conceptual and social strengths of graffiti and street art are rooted in the artists' acceptance of temporality and his or her desire to engage the environment and citizenry directly. As

Simon Hattenstone, a features writer for

The Manchester Guardian, writes, "Since spotting my first few Banksies I have been desperately seeking out more. They make me smile and feel optimistic about the possibilities of shared dreams and common ownership." Insofar as it is truly democratic, the street artist's approach is fundamentally distinct from that of those who aspire to "high art" success. "Fine artists" are essentially aristocratic in inclination. They are the elites who operate within the context of "high art" institutions; their work is most often viewed in

semi-sacred, unlived in spaces, by people who talk about the work in reverent whispers. Street art, by contrast, is viewed by everybody who happens past the artwork. But, today, as the post-graffiti movement sees many of its more celebrated artists entering the "high art" sphere, the populist flavoring of the culture is eroding.

Banksy

Banksy

"Balloongirl"

Artwork on West Bank barrier between Israel and the West Bank

2005Is the aesthetic melting pot a bad thing? The answer depends on your perspective, of course; personally, I'm all for it. Like many contemporary artists, I'm not alone in feeling that my artwork and aesthetic inclinations plant a standard somewhere between the poles of

Juxtapoz and

ArtForum. Just as

I feel torn between my rural roots and the creative community and energy of city life, so too am I drawn to elements of both art orbits, east and west, highbrow and lowbrow. I live and work in New York, so I've cultivated an appreciation for the importance of conceptual heft. But I'm also an erstwhile subscriber to

Juxtapoz who, in my youth, eagerly thumbed through the pages of the

Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Monster Manual, read fantasy novels and comic books, and honed my drawing chops by copying from comic strips. Perhaps I'm biased, then, but it seems that aesthetic commingling introduces hybrid vigor into otherwise "inbred" scenes.

Too many circles of the "high art" world are poisoned by intellectual pretension,

obscurantism, and exclusivity. The

ArtForum world is principally concerned with auction results and art historical significance. In east coast MFA programs, the mills of the contemporary "high art" world, a common question asked of students is, "Where does your work fit in the historical trajectory?" Indeed, at great cost to social legitimacy, the "high art" world has prioritized originality and artistic genealogy.

Much of the "lowbrow" scene, by contrast, is blighted by the artists' focus on disposable pop culture, their willingness to cozy up to the marketing machine, and their populist posturing. In an interview with

Juxtapoz, one young artist said,

"When it comes right down to it, I draw the stuff I like, and people can take it all for whatever they want. I would say that 95 percent is liking big boobs and butts, the other five percent is brain farts that end up in a sketchbook that later ends up as a painting or whatever."

Although I wrote down this quotation without recording the artist's name, I do recall appreciating some of his graphic skill. Still, when I'm confronted with such a thoughtless statement, I can appreciate the animus that brooding, theory-oriented types have for lowbrow art. Where is the evidence of this young artist's vocational mindfulness, his rigorous passion, his poetic sensibility? Of course, his defenders would likely praise his candor, but, in truth, he's posturing as much as the bespectacled, black-clad fellow who insists in his jargon-laden artist statement that

Jacques Derrida informs all of his output.

Marcel Dzama

Marcel Dzama

"Untitled"

2005

Watercolor on paper

14 x 11 inchesDespite haughty sneers from individuals on both sides, it seems to me that the transition that so many post-graffiti artists are making, from the streets to the galleries, could (and should) help create a less sectarian art world. The selfish pretensions of the highbrow art world could be tempered by an influx of no-nonsense, illustrative exuberance, and the lowbrow art world could jettison some of their conceptual superficiality by taking the philosophical and moral obligations of their vocation more seriously. That is, in any case, my hope.

Image credits: Juxtapoz cover image ripped from

Rotofugi.com;; Jeff Soto image ripped from

the Jonathan Levine Gallery website; Judith Schaechter image ripped from

the artist's website; Banksy image ripped from the

Brian Sewell Art Directory; Marcel Dzama image ripped from

David Zwirner website(

Note: This post appeared concurrently on the art blog,

Hungry Hyaena.)

Red Hot Peevish Birds by Resa Blatman

Red Hot Peevish Birds by Resa Blatman Lavish Heronry by Resa Blatman

Lavish Heronry by Resa Blatman

Ravishing The Night by Resa Blatman

Ravishing The Night by Resa Blatman Three Flamingos by Resa Blatman

Three Flamingos by Resa Blatman

NYAXE Gallery visitors view a work of art by Leah Tomaino

NYAXE Gallery visitors view a work of art by Leah Tomaino

Coitus by Resa Blatman

Coitus by Resa Blatman Aphrodite's Garden by Resa Blatman

Aphrodite's Garden by Resa Blatman